Back-to-landers from 1970s are subject of new oral history project

Kickoff event becomes impromptu reunion for those who left the city for the farm life: ‘Some of you I haven’t seen for 40 years.’

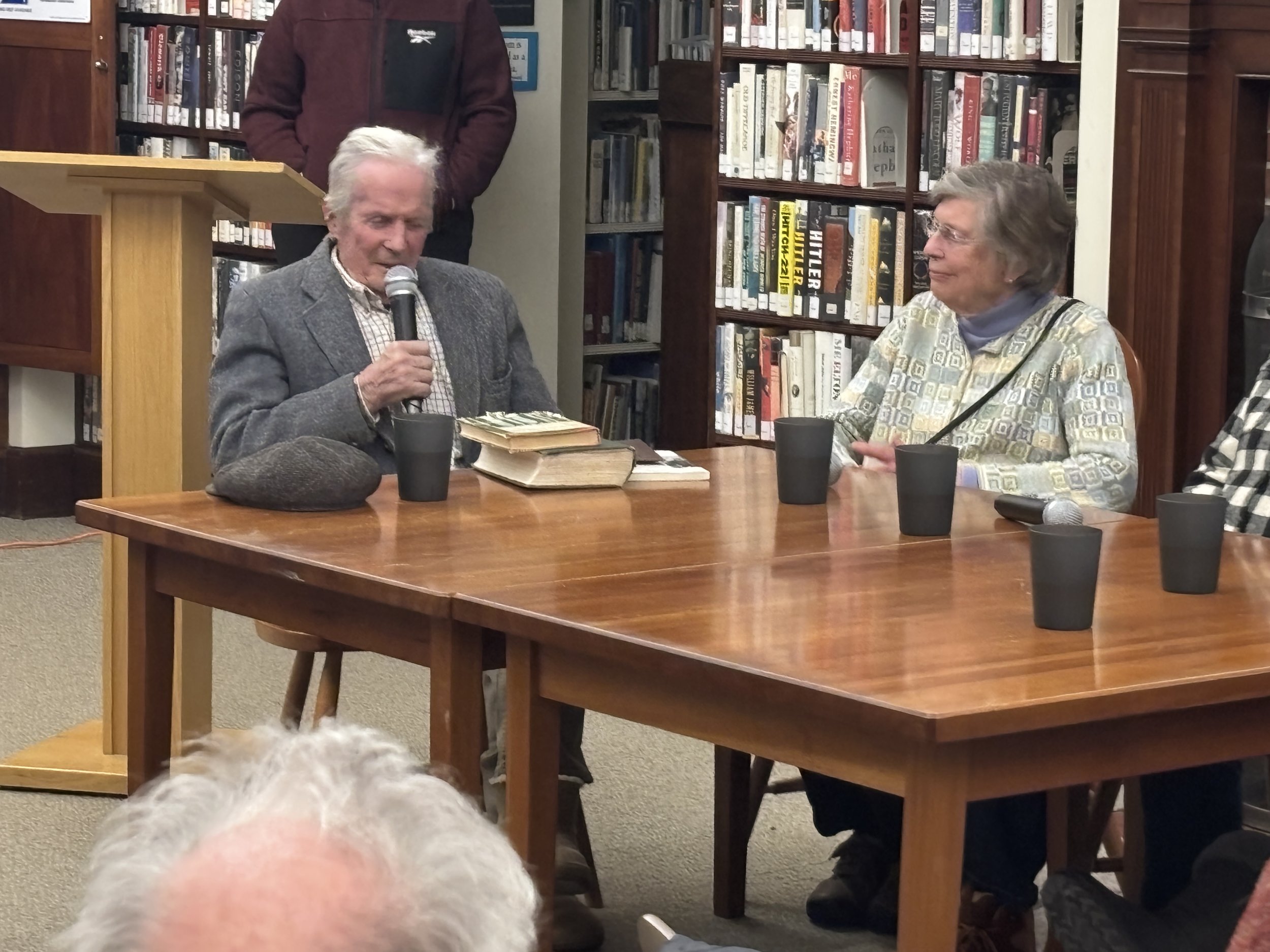

Local residents who were part of the "back-to-the-land movement" in Maine in the 1970s shared their stories to a packed house at the Blue Hill Public Library. The Jan. 27 event kicked off new oral history project by students at George Stevens Academy. Pictured above, from left, are Eliot Coleman, Carole Beal, Jo Barrett, Marjorie Yesley, and Warren Berkowitz. (Photo by Tricia Thomas)

Feb. 4, 2026

By Tricia Thomas

BLUE HILL—Marjorie Yesley remembers pushing an old school bus up a hill nearly 50 years ago, setting it into place on a plot of land that she and a dozen others had purchased to live on. Yesley and several others in the group had come from Cambridge, Mass., intrigued by the “back-to-the-land movement” of the late l960s and early 1970s and determined to hue a communal, self-sustaining life out of the wilderness.

That old bus, Yesley said, was her first home on the peninsula.

“We started out, perhaps, being a commune, but that didn’t last long, and we’ve remained friends, deeply, for about 50 years now,” Yesley said.

Yesley, an artist and homesteader who went on to help found the Bay School, helm the Blue Hill Concert Association and become a champion for the Blue Hill Public Library and other peninsula non-profits, will share her memories with students at George Stevens Academy for a new “back to the land” oral history project to be unveiled this spring.

GSA music and media teacher Phelan Gallagher said students in his audio production class will interview Yesley and others interested in participating during February and March. Recordings of those interviews then will be edited down to four to five minutes each, and serve as an oral history of the movement and its profound effect on the peninsula.

The project is a collaboration among GSA, audio producer Galen Koch of Maine Sound and Story, and the Blue Hill Public Library. It is the second oral history project that Gallagher and his students have undertaken to date. Last year, they compiled and produced an oral history of Blue Hill mountain.

Gallagher kicked off this year’s project with a documentary film screening and panel discussion on the movement, which was held at the Blue Hill library on Jan 27.

The child of a “back-to-the lander” who grew up in Blue Hill, Gallagher said he had originally hoped to entice a dozen or so participants to sign up at the kickoff. When more than 90 people showed up for the weeknight event, Gallagher joked that he needed to revise his plans.

“I think we might need to do more interviews. There are so many people here, and we need to get your stories. Don’t leave without leaving your number or your email,” Gallagher implored the crowd.

An unexpected reunion

For many of those gathered, the event was a joyous reunion.

“It’s wonderful to see so many of us here in the same room. Some of you I haven’t seen for 40 years,” Yesley said.

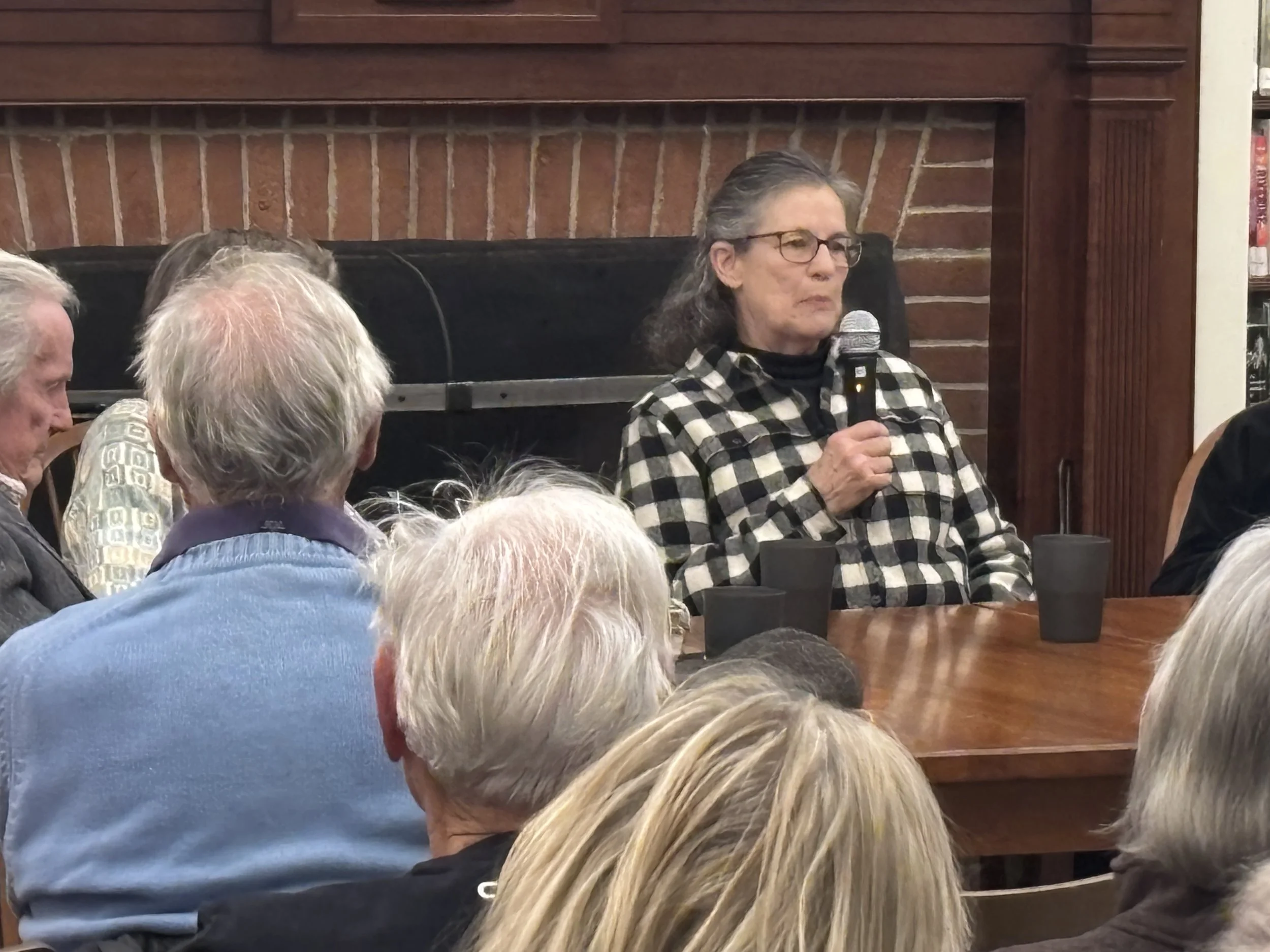

Yesley was joined by local residents Warren Berkowitz, Carole Beal, Jo Barrett and Eliot Coleman, who shared their memories to knowing nods and enthusiastic murmurs of agreement, laughter and a few nostalgic tears from the audience. Except for Barrett, a self-described “outlier” who was born and raised in Blue Hill, all of the panelists came to the area as young adults, eschewing urban life and office jobs for lives derived from the land.

Carole Beal and her husband lived in tents on land they purchased before building a house. Photo by John Boit.

Beal, an artist, moved to the area with her husband, Elmer, after serving in the Peace Corps. The young couple lived in tents on the land they bought while building a permanent home themselves. She credits Elmer, who was raised in Southwest Harbor, with much of their success.

“When we saw this land and all these fields, [Elmer] said ‘Oh, we’ll make hay.’ He had never made hay but, like any Maine man, he could do anything,” Beal said proudly. “He wanted to build a house, and he built a house.”

In the years that followed, Elmer added a barn and other improvements, rebuilt an abandoned tractor piece by piece, chopped cord after cord of firewood, and turned a rough plot of land with 18 inches of rich, glacier-born topsoil into a thriving farm, Beal said.

Beal said that her husband’s MDI roots, and having her in-laws nearby, made the venture a bit easier.

“Being from Maine, it was not the struggle [that others experienced]. We were used to what we were facing,” she told the audience.

Eliot Coleman, left, credited his success as a farmer to a neighbor’s enormous pile of horse manure. Photo by John Boit.

Eliot Coleman, a farmer, entrepreneur and author, said that his love of adventure led him to the peninsula. After whitewater kayaking, ski racing and rock climbing, Coleman picked up a copy of “Living the Good Life,” a book written by back-to-the-land pioneers Helen and Scott Nearing, who came to Brooksville’s Cape Rosier in the 1950s. It was the Nearings who gave Coleman his start here, selling him 60 spruce- and fir-covered acres on Cape Rosier that he slowly turned into a pristine organic farm.

Coleman also credits the generosity of horse farmer Billy Tapley, and regular trips to Tapley’s manure pile, with helping him turn his cleared land into fertile beds for both household and market gardens.

“It was the hugest manure pile I had ever seen in my life, and it was mining that [manure pile], shoveling it into a trailer behind my 1942 Jeep and hauling it back to the farm that allowed me to turn that poor, almost non-existent soil into something that would grow crops,” Coleman said, adding that “thanks to [the Nearings] and thanks to Billy Tapley, I’m here and I have a farm.”

A community that coalesced

As a kid, Barrett would spend “hours” roaming outdoors with her dogs, she told the audience.

Jo Barrett “always liked being outdoors.” Photo by John Boit.

“I always liked being outdoors and making my own way out there,” she said.

Barrett, whose mother was an avid gardener, graduated from GSA in 1972. She remembers vividly when “new folks” started arriving in town.

“I was already very interested in wild edibles, in eating outdoors and survival camping, winter camping, all that jazz,” Barrett said. “But, I can’t even tell you how exciting it was when these folks started showing up—these really interesting people whose ideas and values just resonated with me. I just made a lot of friends right away.”

Although Barrett describes herself as a “homesteader—not a back-to-the-lander,” she still cherishes the friendships she made with the newcomers.

“Getting to know all of these people was just so stimulating,” she said.

Berkowitz, a former special education teacher, said he moved to the peninsula seeking a “community.”

“At first, a lot of people weren’t very comfortable with the back-to-the-landers coming in. We all have stories related to that,” he said. “But, once we had kids, once we got involved in the school, in coaching Little League and pee-wee basketball, it really started gelling into something that we were really feeling good about and part of.”

Berkowitz said that he and other young transplants formed a community, which provided tangible and intangible support to each other as they settled in, assimilated and forged their new lives here.

“The homesteaders would help each other do projects, and we’d have parties and would do things together. That really created a very positive aspect for me, as someone who really ‘grew up’ in many ways when I got to Maine,” he said.

The oral histories collected by Gallagher’s students will be archived permanently on the Maine Sound and Story website. They also will be unveiled to the public at an event at the library in late April. Gallagher said he hopes the project brings to light how pivotal the back-to-the-land movement was for the area.

“This place would not have been what it is today if that had not happened,” he said.